A new laser paradigm: An electrically injected polariton laser

“It is no longer a scientific curiosity. It’s a real device.”

Enlarge

Enlarge

ANN ARBOR—Engineering researchers at the University of Michigan have demonstrated a paradigm-shifting “polariton” laser that’s fueled not by light, but by electricity.

Polaritons are particles that are part light, and part matter.

“We report the first electrically injected polariton laser—a truly transformative result,” said Pallab Bhattacharya, the Charles M. Vest Distinguished University Professor of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science and the James R. Mellor Professor of Engineering, whose paper on the work is published online in Physical Review Letters.

“Since the proposal of such a device in 1996, researchers around the world have been trying to demonstrate it. It is no longer a scientific curiosity. It’s a real device.”

The new device requires at least 1,000 times less energy to operate, compared with a conventional laser, Bhattacharya says. He envisions its eventual use in any application where a laser is used today, such as in the optical communication field for wired Internet and in the medical field for surgery.

And as transistors—the building blocks of computers—reach their fundamental size limit over the coming decade, Bhattacharya says lasers like this one that are low-power and easier to modulate could play new roles in consumer electronics.

“Some of the communication on the chip and from chip to chip is going to move to optical communication, or lasers,” Bhattacharya said.

Technically, “laser” is a misnomer for the new device. The word is actually an acronym for Light Amplification by Stimulated Emission of Radiation. A polariton laser produces a coherent beam of light in a different way.

“The physical process is Light Amplification by Stimulated Scattering of Polaritons,” Bhattacharya said.

Enlarge

Enlarge

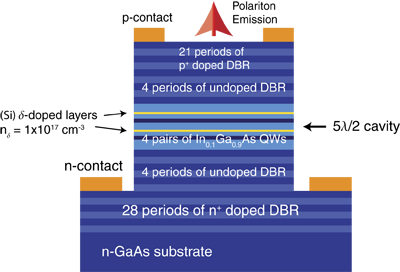

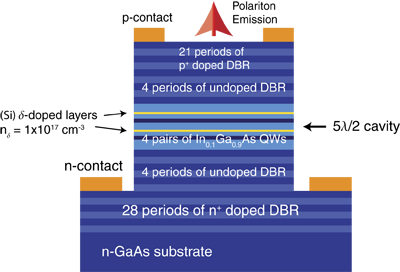

The researchers generated polaritons by using electricity to excite samples of the semiconductor gallium arsenide in a microcavity under certain conditions. The polaritons quickly decayed by transferring their energy to photons, which, due to properties of the original polaritons, escaped the cavity as a single-colored beam of light.

“Our success is based on two novel features,” Bhattacharya said. “First, we deployed additional electron-polariton scattering to enhance the relaxation of polaritons to form the coherent ground state. Second, we applied a magnetic field so that more carriers can be injected with the bias current without losing the required conditions for polariton lasing.”

This laser must be at cryogenic temperatures to operate, but Bhattacharya and his colleagues are working on a room temperature version.

MENU

MENU